As far as we have come, we may be ready to start developing. For now, we know how to use the camera, we also told something about darkrooms, and then a little about developing tanks. The next logical step is going to be doing the develop itself.

The process to develop a photosensitive material is the procedure, in which, we are going to bring the images that are stored in the film, and making it no longer sensitive to light.

You may look on internet, and almost everyone is going to have it's own developing process, this is because we are free to experiment as much as it suits one. that is why I would like to explain what I think is the standard process. I also will highlight the steps that must be done, and explain why some are kind of optional.

- Presoak

- Develop*

- Stop Bath

- Wash

- Fix*

- Wash

- Hypo solution

- Final rinse*

- Coating

- Dry

The entries marked with the * means that they must be done.

Presoak

This step is intended to be done with water. This is to clean the film from any dust particle, finger marks and humidifies it so the developer will not act suddenly. We need to agitate the tank, with water, at least for 30 sec.

Develop

The whole process is around it, and this is going to be the chemical in charge to bring the images stored in the film and become visible, but not just free from light sensitivity (if we take our film out of the tank it will be ruined as the light will still react with the emulsion).

But when you go to the photo store, and you say to the store clerk: "Could you give me a developer?" he immediately will reply "Which one Mr./Mrs.?". So yes, there is going to be a developer from each major brand, and within the brand they may have several, and each one could be able to be mixed in different ways… what a haze!

A starting point, and one that I recommend most, is to search our film's user manual. This ones do not come with the film in the box, so google it! (the key words are the brand, the name of the film and fact sheet). But for now on I will explain about my own experience with the developers I know. As a big part of the whole, most developers are designed so they work perfect at temperatures between 20 to 24 º C (68 to 75.2 F). I most often try to use the developer as nearest to 20 ºC (68 F), in future references this is going to be the temperature.

Also very important to have at hand, is the developing chart for our film, this one most of the times comes with the original packaging.

Types of developers

Single use

There is a family of developers that will only work for once, and then we have to dispose them. The most popular of this kind of developers is Kodak's D-76. This developer is quite easy to mix, we only heat 3 liters (0.79 US gal) of water until 52 ºC (125.6 F), pour the powder that comes in the packaging, once all mixed ad more water, 0.8 l (complete the US gallon). When the temperature goes down to room temp. ca. 20 ºC (68 F), we now have a developer in stock, meaning that is at its purest dilution. We are going to be able to mix it with water so we reduce its developing power for making more "softer" processes, in which we could bring more details, but at cost of our contrast.

In this type of developers we may see something like this on the developing chart 1+0, 1+1, 1+3. What do these mean? This is a sum, in which the first number is the quantity of developer we need plus the quantity of water we are going to use to dilute.

1+0 means that we are only use the chemical

1+1 means that we are going to use half developer, half water

1+3 means that we are going to use one part of developer and three of water

Are some developers like Agfa's Rodinal (I do not like it) that uses dilutions like 1+59, 1+60. But how do we know how much do we need. Well, in the bottom of the plastic tanks it says something like 135 x 1 = 300 cc, means that for one 135 film we need at least 300 cc (cubic centimeters) of developer, 100 ml (nearly 10.2 fl. oz.), so 300 is our goal, and we want to do a 1+3 dilution. The first step is to divide our goal by the sum of the 1+3, is 4, so 300 divided by 4, that equals 75. The next step is: we need one of developer plus 3 of water, 75 multiplied by 3 is 225, we take that and then ad the 75 of developer we needed an now we have our developer in 1+3. Single metal tanks need 250 ml (8.5 fl. oz.).

Once our developer is ready for the job, we pour it in the tank, put our clock in the time the chart indicated, at the right temperature, and we start the process. Regardless the type or the brand of developer one of the most recurrent habits is to agitate the tank, there is fact sheet recommendation, that tells us to agitate the tank 10 seconds each minute. You can agitate more often, just to blow up the grain, but you can not do it, this helps that the development process occurs as even as posible. As we cycle the particles inside, moving fresh chemical near the emulsion.

Just one the clocks hits zero, we toss it to the drainage. And be ready to pour the next chemical, but for now is time to explain about the other kind of developer.

Multiple use

It may seem a little bit logical, this developers are able to work even after certain number of uses, this developers are once prepared and there is nothing else to do. The most common developers are Kodak's HC-110 (dilution B, is for film) and T-Max, Ilford's ID-11 and Microphen. These four can only hold 10 processes, after the tenth the results are uneven.

The only problem with those is that with each use the developer looses it power, but it can be compensated with more time. For example with HC-110, we have used it like 6 times, for each use we add 10 seconds to the chart time, this means, if the chart says, the film develops with 5 min, we add sixty seconds to it, a whole minute, our develop time will become 6 min.

While with Ilford is a little bit different, in this case we have to ad percentages, for example it is going to be the 8th process, so I have to ad the 70% of the original time, in this case 8 min. the 70% of 8 is 5.6 min, so we have to sum it to the original time, 13.6 min is our developing time.

Just as a little note, ID-11 and Microphen can be diluted, if we do so, they will become single use developers.

When you become more familiar there exist other classifications to developers, multi-propuse, fine grain, being the most common. In this case I recommend giving each one a try to find the one that likes you most.

Stop Bath

This chemical is the easiest one to prepare and can be switched with vinegar. The job is going to do, is to stop the effects of the developer, so our developing time comes as closer as the chart says. It will only work for 30 seconds and we have to agitate all the time.

Wash

This little wash is to clean all the residues could be left during the developing and the stop bath, it is made with tap water, and it lasts 30 seconds with constant stir.

Fix

The second most important step during the process, this chemical will transform the silver halides to silver salts, that are no longer sensitive to light. So once the film is bathed with this, it will become light safe, you cant take it out and nothing will not happen. It will also give the longevity to your processed film, a well done fix will make your film endure at least 20-30 years.

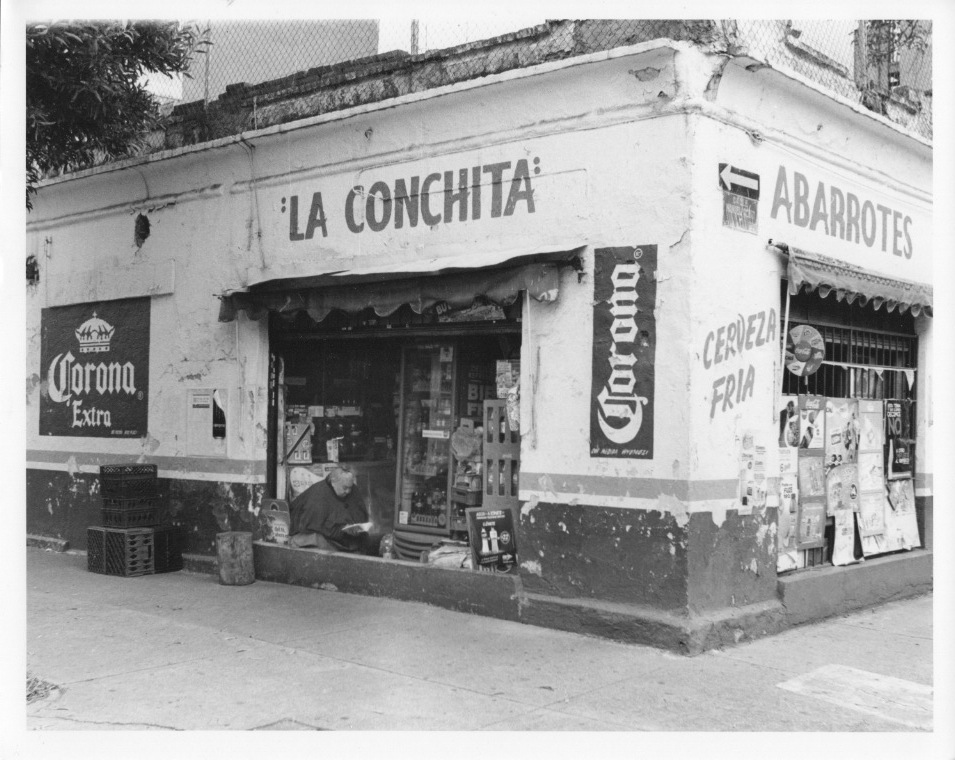

The fixer I found most easy in Mexico City is the Rapid Fixer from Kodak, I do not know any other, so I am not able to tell you if is fast or no, but I can tell you that it is working properly or not. The time I recommend for the fixing process is to let it be in the tank for at least 10 minutes, with the same agitation scheme as with the developer. You can take out the film and if it is still purplish it still needs fixer, if more than 20 min with this, that means you need to change your fixing solution with new.

Rapid fixer for film is easily prepared, it comes in two bottles, the fixer and a hardener, use 1.9 liters (0.5 US gal.), pour the fixer bottle, mix it well, pour the hardener bottle, mix well and ad enough water to fill 3.8 liters (1 US gal.). This will endure as long as six months in a well closed bottle.

Hypo solution

The fixer tend to left undesired residues on the film, that will cause stains in the emulsion, so this Hypo solution will help to wash it quickly. Before pouring the Hypo, do a wash, just like the one before the fix process.

This Hypo, here, it is sold in small bags, to prepare just one liter (33.8 US fl. oz.), just heat water, pour the powder, mix it, and presto, you have Hypo solution.

During the process it just needs two minutes with the same agitation scheme as the developer.

Final rinse

This is done with tap water and the time will depend on the usage of Hypo solution, if it was used you have to add water for five minutes, changing the water each minute. With the same scheme of agitation as the developer.

If you have not used Hypo solution, be prepared to left the film almost a day in water, and keep changing the water at least one hour, agitation… try to do it from time to time. This step must be done to wash the film from any residue from the steps before.

Coating

With time, Kodak, created a chemical called Photo-Flo, that is aimed to protect from small scratches and make the emulsion static free, so dust will not stick to it. Also gives the film a shiny finish to it. In this case left it one minute and any agitation, this chemical is soapy, so it will form foam if stirred, so avoid it.

Dry

The last part of the whole process, find a place to hang the film, cloth clippers are good for this, and do not forget to use a counter weight to keep the film stretched and avoid the natural curvature. The drying time will depend on where do you leave it, but for most of times it will take 30 min to one hour.

This has been the steps I usually do to develop a film, as said before there are some steps that are not essential, but aid in making the process cleaner and leaving better results. The next question is how to keep you film, in the US is a brand called Print File, they manufacture special sheets with sleeves to preserve the strips. I think they are the most easy to find and economic too. Just do not forget to find a dry cool place at your house to preserve your films, as humidity will damage them.